|

Beyond Ignorance: The US Orientation toward China and Russia

By

Akihiro Iwashita

*The article was written

at the end of July, 2008, and

originally published in Spanish (translated from the English text) in Vanguardia

Dossier, 29 Octubre/Diciembre 2008. After the conflict between Russia and Georgia

over South

Ossetia at the beginning

of August, a kind of anti-Russian rhetoric has prevailed in

Washington

DC

.

No matter how noisy the emotive campaign is today, the basic interests

of the

policy community tends to focus exclusively on the places in which the

US

military is

directly involved. Little has substantially changed toward Russia and

China

.

Rather, if any lessons are

to be learned from this matter, the US

should learn the importance of going beyond its usual love-hate

relations with

Russia

.

The US is now

paying a hefty price for its long time

ignorance toward

Russia

.

Simply calling

Russia

a “partner” without showing the proper respect was a mistake that US is

now ruing.

――――――――――――

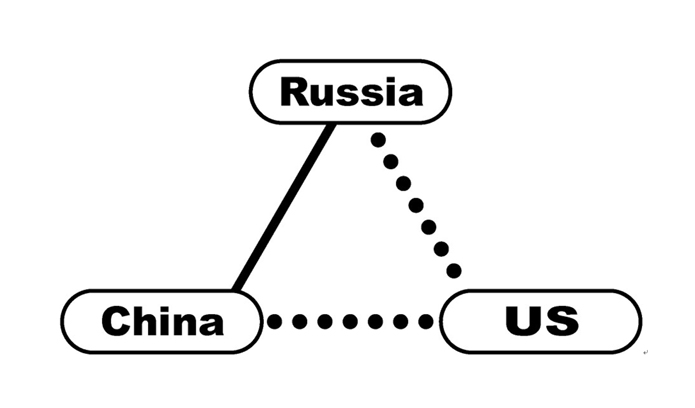

You may think that the US is concerned about the emerging

autocratic

regimes of China

and Russia and

their collaboration in areas

stretching from Northeast Asia toward Central Asia against the US.

Reactions in

Washington

DC

have

been a bit odd, however. The true

challenge for the US

foreign

policy community to overcome is its seemingly total lack of concern

over Russia and

China

.

This challenge seems to have

taken a back seat to “international terrorism” and the Middle East. How to get the US

foreign policy properly involved in China,

Russia

and the related region is an urgent task with global implications.

A Forgotten Area

"A little on China.

No Russia."

This is the reality I

recognized from the current US

foreign policy orientation during my recent ten-month stay in

Washington, DC

.

Frankly speaking,

Washington

"forgets" their presence in the world. Clinging on to on-going

"wars" in Iraq and Afghanistan,

they are more

enthusiastic about reshaping the military, its support of Pakistan against the Taliban, deterring

Iranian

provocations on nuclear development, and building peace between

Israel

and Arab

countries. It does make some sense for the US

to focus on issues and areas in/around the Middle East and South Asia,

two

areas keen to be considered as the interests of the

US

nowadays.

The US

seems to pay little attention to the relatively "peaceful" area of

Northeast Asia, though it contains the nuclear ambitious

North Korea

.

U.S.

President George W. Bush’s and U.S. Assistant Secretary of State

Christopher

Hill’s recent "new" approach toward North

Korea has perplexed the Washington

community, especially since it seems to mirror that of the Clinton

administration's past diplomacy toward

Pyongyang

. Alas

for

China

.

Despite the strife in Tibet

last May, Bush has declared his intentions to attend the opening

ceremonies of

the Beijing Olympics. Where have Bush's courageous remarks on "regime

change" or "democratization" in the region gone?

In contrast,

Bush's attitude toward Iran

has been long tight and harsh, mostly

passing some moderate recommendations on engaging Iran on the nuclear issue,

though

the recent visit to Teheran by undersecretary of state William Burns

might be a

beginning of a policy

change. His policy toward

Iraq

shows no change. The Bush administration projects a tough image

in/around the

Middle East, while conducting a mild foreign policy approach toward Northeast Asia. The difference in attention

given to the

two regions is huge. The latter region appears to have dropped out of

the minds

of

Washington

policy makers.

Different Strokes

China is,

nevertheless, the main topic to be discussed within the

Northeast Asian policy community in

Washington

DC

.

One reason is that China

has been thought of as an invisible

competitor with the

US

in the region. Another one is that China's

power both economically and militarily is developing rapidly, and

presents a

challenge to the global leadership of the

US

. All of them agree that

China

and other

related matters are important, but no consensus has been reached on how

it

should be managed. Most Republicans prefer to hedge against China's upsurge through the US-Japan

alliance

while some Democrats want to collaborate directly with China to stabilize the region as a

stakeholder

or build a multi-lateral architecture with China

and

Japan

.

Japan's

presence is not seen

on the surface of the discussion even if they understand the alliance

as a

necessary tool to either compete or cooperate with

China

.

In turn,

Russia has little presence in the debate

within this community. Northeast Asian policy circles almost completely

ignore

its positive contribution and collaboration in the region though Russia works with the

US

and

other colleagues on the

North Korean nuclear issue within the Six-Party talks. The US conventionally works together with China to push

North Korea

to dismantle its

nuclear facilities. Within the Six-Party talks, the interests of Japan and

South Korea

are considered,

though

not adequately. Unfortunately,

Russia

's

voice is rarely heard. As matters concerning Russia

are usually considered a Europe related issue, observers seldom think

of

Russia

in a

Northeast Asian framework. Second, matters concerning Russia are usually brought up during

discussions

about European expansion, Kosovo's recent declaration of independence,

eastern

enlargement of NATO toward the Ukraine

and Georgia, CFE and the Missile Defense plan in Central

Europe.

How does the US

approach

Russia

?

From my observation, Russia's

arguments and interests are not seriously taken into consideration

within European

policy making circles. Few in the policy-making community fear Russian

pressure, although former Russian President Vladimir Putin often

criticizes and

worries the

US

.

They share the view that

Russia

's

complaining and threats are of nominal concern. Of course, some

lobbyists place

an emphasis on a "new Cold War" discourse and urge the US to act more aggressively to impress

upon Russia

the importance of democracy and human rights under the current

Putin/Medvedev regime.

But their arguments have had limited appeal and are rarely taken

seriously.

The

US

Coolness

Beside that,

the US

has not responded seriously to the Sino-Russian "strategic

partnership," which has developed since 1996 onward and is often

interpreted as a collaboration to counter against the

US

influence

over the world. First, from Washington's

point

of view, differences in geopolitical interests between China and Russia are apparent. China does not share Russia's

worry over NATO and, rather, does not necessarily support Russia's position in Europe if it

brings about

an unwanted reaction toward China

in Asian affairs. Russia,

in

turn, does not hope for China

to strengthen its state power too much in Northeast

Asia.

Instead, Russia

would rather

engage with Japan

and the

two Koreas to build

a

regional multilateral interaction to keep the Russian Far East, the

weak flank

of Russia vis-à-vis

China,

stable and safe. Russia

also

does not wish to be involved in accidental matters, which could provoke

a fatal

conflict between the US

and China such as

on the

Taiwan

issue. Indeed, the

partnership occasionally works in areas in which the two powers have a

shared

interest such as their rejections of UN sanctions against Zimbabwe and

Iran

in the UNSC. But there are not

many such cases. Contradictions always appear to coexist with

cooperation in

the partnership.

Second,

Washington

does

not believe that the

partnership is value-oriented. Even if China

and

Russia

currently have autocratic regimes, it is difficult for them to work

together on

the basis of shared values as democratic countries do, particularly, in

times

of war. "Autocratic" cooperation has its limitations per se as they

seem to be marriages of convenience. It goes along well only when they

face a

common "threat." Geopolitical differences often hinder collaboration

since there is a lack of shared values within the partnership.

A point of

contention between China

and Russia

is Central Asia. There may be some

shared

interests between them, namely, keeping the region free of

disturbances. Both

have deep concerns over a would-be trans-border force such as

"terrorists," "separatists" and "extremists," on

one hand, and toward the US,

a superpower that could intervene in the affairs of Central Asia, on the other hand.

However,

Central Asia is beyond the joint

control of China

and

Russia

.

The two

middle powers function in the region: Kazakhstan

prudently keeps good ties with China

and Russia but also

shapes

relations with the US,

EU,

Japan

and other

great powers under a multi-vectored and balanced foreign policy. Uzbekistan, often swinging between the

US

(such as

after the September 11 attacks) and the Sino-Russian "camps" (such as

after the Andijan Incident in May, 2005), sticks to play an independent

role in

the international field. Even Kyrgyzstan

and

Tajikistan

,

small powers in the region, bandwagon the Uzbek or Kazakh path to enjoy

more

freedom from their giant neighbors in/around the region. After 9/11, Kyrgyzstan succeeded in acquiring the

status and

financial support from the US

in exchange for providing an airbase for

US

forces operating in the

region.

After resolving their territorial issue with China and supporting the

US

military operations against the Taliban both since 2002 onward,

Tajikistan has

gained much more substantial support from Russia, which wanted to

offset the

regional influence of both China and the US, while maintaining its

military

presence in the southern front of the Central Asian sphere next to

Afghanistan.

Against the

backdrop of diversity and the

present dynamics of the Central Asian regional alignment, China and

Russia

compete to

strengthen their

political influence and economic rivalry over the region. The notion of

a

"Great Game" among Russia,

China

and the

US

as fashioned

in the nineteenth century is an exaggeration because Central Asian

countries

considerably enjoy their own initiative and interests in the region.

But to the

eyes of the great powers, competition looks more severe because of the

independence Central Asian countries.

Energy

cooperation on oil and gas between China,

Kazakhstan

and Turkmenistan

often

irritates Russia

while Russia's

political and strategic overplay in the

Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a Central Asian based security forum

with India, Pakistan, Mongolia

and Iran as

observers, makes China

uneasy about a future confrontation with

the

US

and other Western countries.

Getting China

and Russia Right

for Peace

and Stability in

Eurasia

Back to

Washington

.

First, most US policy makers

show little concern over the Sino-Russian "strategic" cooperation,

particularly, in the context of an anti-American orientation. Second,

if they

were asked which country could collaborate with the US,

the majority of them identify

Russia

as a partner. Policy communities in the State Department, National

Security

Council and other experts belonging to various think tanks do not worry

much

about Russia but do

share

some concerns over the future of

China

. Daniel Fried,

assistant

secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, mentioned that

Russia is

not considered a "revisionist" state and, rather, is viewed as a

would-be partner to offset the influence of a revisionist power in the

Pacific

(undoubtedly, he means China). In a global sense, Russia

shares strategic interests with the

US

on defense and nuclear

issues.

He also confirms that the US

could manage every issue on the table such as Kosovo's independence and

the

missile defense program with

Russia

except anti-US feelings in the Russian public. In turn, regardless of

Chinese

feelings toward the US,

they

may think that it is not an easy task to handle problems related to

China

.

Even

some China experts

in the

Northeast Asian policy community, who are generally thought of as

"pro-Chinese," express concerns about

China

and place an emphasis

on the

US-Japan alliance in candid conversation.

Some Central

Asian experts are the

exception. They may prefer collaborating with China

to collaborating with

Russia.

However, firstly, most of them, coming from a Russian studies

background and

familiar with the thinking of Russia,

do not fully understand what

China

was, is and will be. Secondly, they overly depend on China

to offset Russia's

dominance

owing to the temporary fact that China's

presence is still weaker in Central Asia than

Russia

's. The idea that the Sino-Russia partnership is

a threat to US interests, as Dr. Stephen Blank of the Army

War

College

often proposes, is out of the mainstream of the

Washington

policy-making community.

Foreign

analysts do not need to pay much attention to this sort of discourse.

The problem

with the US foreign

policy toward China

and Russia

basically arises from an almost complete indifference and ignorance of Russia's interests, "fragmental"

concerns toward

China

,

and a lack of will to truly understand the nature of the Sino-Russian

partnership. The Sino-Russian partnership was recently created during

the long and

complicated process of overcoming historical and geopolitical

challenges,

including border wars fought in the nineteenth century and 1960s. China and Russia,

struggling with bilateral coordination, have little room to realize a

partnership against the

US

and other targets. Rather, the contributions the partnership has made

to

Eurasian security and stability should be appreciated. Then, how the

partnership should be engaged with US interests is a main area of

concern.

However, the

Bush administration did not

accept a multi-national approach of foreign commitment toward any

region. Even

the recent "rapprochement" with North

Korea is just a small sign of change from the

past, since

the Bush administration basically depends on direct talks between the US and North Korea. Unfortunately,

only a

slight show of concern for the other countries involved within the

Six-Party

talks is shown. The Bush administration officially keeps its faith in a

bilateral oriented approach toward the region.

A US

presidential candidate, whether

Republican or Democrats, must realize the failure of Bush's approach

toward the

region and return to a multi-lateral foreign policy to some extent.

Presumptive

Democratic presidential nominee Senator Barack Obama's foreign policy

team

could push the orientation in a more substantial way. Undoubtedly, a

new

multilateral diplomacy of the

US

would be a welcome change to the international community. The Six-Party

talks

could develop in a multi-lateral architecture in Northeast

Asia under his foreign policy team's initiatives.

Considering

Sino-Russian collaboration in Central Asia,

the Shanghai Cooperation Organization should be a target to work with,

even if

it serves still, however weakly, for regional security. Recently, even

under

the Bush administration, the

US

attitudes toward the SCO has changed from its previous position of

passing over

its existence and suggested the possibility of cooperation in the

region. When

the geopolitical positioning of the SCO, engaging Iran

and contact with Afghanistan,

is considered, cooperation could ease the burden that the

US

carries in

its battles against the Taliban and al-Qaeda. How to rebuild a

post-Bush

foreign policy of the US

toward China and Russia is one of the key tasks for

strengthening

global collaboration beyond either Northeast Asia or Europe.

Eurasia is the area that has yet to be discovered by US

foreign policy. The EU and Japan

naturally have a proper clue as US allies

to get the US right

in

reshaping the world together through a multi-lateral framework which

includes China and

Russia

.

Akihiro Iwashita,

Director and Professor of the Slavic

Research Center, Hokkaido University, Japan, was Visiting Fellow of the

Center

for Northeast Asian Policy Studies at the Brookings Institution, US

(2007-2008).

*The views expressed in the essay belong

solely to the author and do not represent the official position of any

organizations to which the author is permanently or was temporarily

affiliated.

[index]

|